In many respects, Nepal is an ethereal realm replete with massive mountains draped with snow and antiquated temple structures: it’s an earthly museum of the history, culture, and resilience inherent in it. Nestled between the Himalayas, India, and China, this small country has witnessed races and races of mighty dynasties, great spiritual revolutions, wars, and social turmoil that forged an identity for them. There are Major Historical Moments of Nepal that shaped Nepal today.

It is a long history, unlike most countries, which has a more or less straight storyline; Nepal’s history is woven into assorted ethnicities, religions, and political changes. This is the true point of uniqueness for such a country- how its people have thrived through different eras of monarchy, autocracy, civil conflict, and democracy. Each decisive moment in this country reflects not just on past rulers or revolutions but also tells about the soul of a nation that is in the effort of definition.

Understanding Nepal requires something more than just rare dates and names. It requires stepping into the moments that essentially redefined being Nepali. It talks about historical moments between the peaceful birth of a spiritual leader and bloody revolutions that brought down regimes. This is a deeply human history-the history of kings and commoners, a history of warriors and monks, and finally a history of rebels and reformers across time. These events continue to reverberate in the political, cultural, and international realities of the nation itself. This will now take a deep plunge into seven events that transformed Nepal into the dynamic and diverse land it is now.

Historical Events of Nepal

1. The Birth of Buddha – A Spiritual Revolution Begins (c. 563 BCE)

One of the Major Historical Moments of Nepal starts more than 2,500 years ago, in the pristine gardens of Lumbini in southern Nepal, a boy named Siddhartha Gautama was born to Queen Maya Devi. This child would later come to be known as the Buddha, “the Enlightened One,” whose teachings on suffering, compassion, and mindfulness would touch the lives of billions across Asia and the world. Born in royal privilege, Siddhartha renounced the life of a palace to delve into the deeper truths of life and existence. His path culminated in his enlightment under the Bodhi Tree, a moment that witnessed the birth of Buddhism, a culture and faith of peace, detachment, and inner liberation.

Buddha arose with his new order in a very rigidly ritualistic and caste-dominated setting. His messages of equality, non-violence, and compassion appealed beyond the caste barriers and made Buddhism a revolutionary movement. Though he remained primarily in India, he invoked great national pride for the teachings originating in the land of his birth. Today, Lumbini is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and international pilgrimage center, luring millions of visitors every year. The gentle teachings of Buddha continue to influence the Nepalese identity and soft diplomacy.

2. The Unification of Nepal – The Vision of Prithvi Narayan Shah (1768)

Before about 1750, what is today considered Nepal was a conglomeration of dozens of small kingdoms, which were often at odds with each other. It was into this fractured arena that Prithvi Narayan Shah, the very ambitious king of Gorkha, came. He envisioned a united and independent Nepal and launched a daring campaign that began in 1743 and culminated in the historic conquest of the Kathmandu Valley in 1768. He combined conquests with diplomatic moves, a tremendous grasp of the war and politics of the day, especially the growing influence of British India.

With Nepal seen as a “yam between two boulders,” a term alluding to her weak geographical position in between two cantankerous empires, Prithvi Narayan Shah advised that the rulers would henceforth secure the independence of the kingdom they would rule by not getting into any foreign entanglements, especially with the British East India Company. This was one of the Major Historical Moments of Nepal.

The rule of Prithvi Narayan Shah set in motion events that would lead to the making of modern-day Nepal, having established a centralized monarchy to rule over its lands for the next two centuries. The process of unification was brutal at times but very effective in transforming Nepal into a strong, singular kingdom from disparate principalities. His legacy persists in the consciousness of Nepalese nationalism, and his portraits adorn government offices and classrooms.

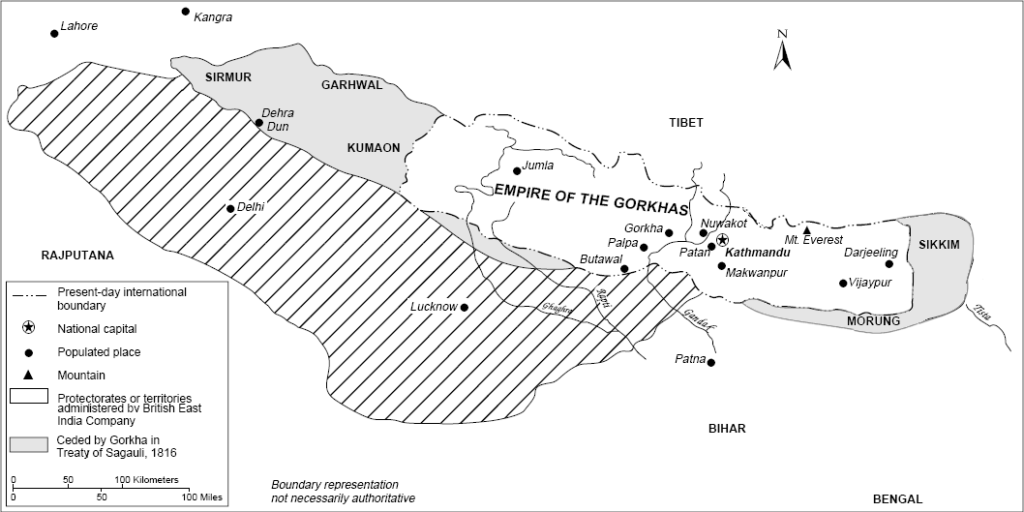

3. The Anglo-Nepalese War and Treaty of Sugauli – A Price for Sovereignty (1814–1816)

Expanding further into South Asia, the British Empire eventually came into a conflict with Nepal over territorial boundaries. Tensions rose into the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814 to 1816 between the Gorkha Kingdom and the powerful British East India Company. The British were ultimately able to overpower the Nepalese army, who fiercely resisted with legendary bravery—especially the Gorkha soldiers—with superior weaponry and organization. The war ended in 1816 with the signing of the Treaty of Sugauli.

This treaty was disastrous for Nepal. The country lost territories of great significance, such as Sikkim, Kumaon, Garhwal, and parts of the Terai, all of which diminished its influence and resources. However, unlike many other states in the region, Nepal maintained its independence and was never fully colonized—mainly due to the British interest in keeping Nepal as a buffer state.

In return for agreeing to accept a British Resident and direct its foreign policy to British interests, Nepal got to keep its independence. Although an unfortunate turn of events, it was also Nepal’s formal entry into the geopolitics of the colonial age, which demonstrated that its leaders could be quite resilient when it came to preserving independence at a huge cost. This event shaped Nepal in many prospective and became one of the major Historical Moments of Nepal

4. The Rise of the Rana Regime – A Century of Hereditary Rule (1846)

With the Kot Massacre of 1846-a virulent political massacre-all politics in Nepal underwent an overnight face wash. Jung Bahadur Rana, a military commander and political strategist, slaughtered dozens of nobles and rivals for the sole purpose of gaining power, thus rendering the king a mere ceremonial figure. And thus was born a dynasty of Rana hereditary Prime Ministers, who ruled Nepal for over a century and enjoyed absolute power. The monarchy became a mere symbol, while all real power was centralized within the Rana family. It is a iconic event in Nepal’s history.

Nepal was becoming more and more isolated during the years of Rana rule. Although they slowly came to terms with modernization, education was practically reserved for the elite. The Ranas maintained internal stability nonetheless and built some of the country’s earliest infrastructure, like roads, palaces, and administrative buildings. Their alliance with the British only further fortified their rule, rendering them virtually untouchable. Slowly, however, the discontent began to brew in the shadows. Intellectuals, commoners, and even some royal members began to demand change-taking the first steps toward Nepal’s first democratic awakening.

5. The End of Rana Rule – Dawn of Democracy (1951)

After more than a century of despotism, the control of Nepalese village communities and extra-rulers led by King Tribhuvan revolted against the Rana regime in 1951, aided by exiled politicians. This movement is popularly called the Democratic Revolution, which aims to demolish hereditary rule and establish parliamentary democracy. The turning point was King Tribhuvan’s advent into India, joining hands with the democratic forces. Having faced a growing tide of popular discontent and mounting international pressure, the Ranas agreed to share power, though reluctantly.

This coalition formed a new interim government, consisting of both Rana and democratic leaders in their first attempt at participatory governance in Nepal. Though fragile and unstable, the formation of a coalition government meant an end to the long-drawn autocratic rule and a beginning for the democratically installed government.

A constitution was to be promulgated, elections were to be organized, and for the very first time, there was going to be some say from the common Nepalese people concerning the governance of the land. But unfortunately, internal divisions among leaders and the lack of political maturity resulted in constant shifts in leadership, preventing the realization of that dream of a stable democracy. Nevertheless, 1951 endures as a building block for the modern political history of Nepal.

6. The People’s Movement (Jana Andolan) – Revolution of the Masses (1990)

By the late 1980s, growing disenchantment was felt about the panchayat system, run by King Birendra as an absolute monarchy dressed in the garb of guided democracy. Inspired by the global waves of democratization, especially those in Eastern Europe, the Indonesian students, civil society groups, and opposition parties in Nepal all joined together in 1990 into what they branded the Jana Andolan (People’s Movement). Waves and waves of big protests, strikes, and demonstrations then rolled across the entire country. After weeks of nation unrest, King Birendra agreed to lift the panchayat and adopt a constitutional monarchy.

Words were written in an entirely new constitution that proclaimed the rights of freedom of speech, recognition of multistate, human rights, and independence of the judiciary. Hence, for the first time, Nepal has wholly witnessed a glorious and vibrant competition in elections and civil society. The transition is, however, far from being complete. The democratic experiment is infected with corruption, instability, and intra-party conflict. True, the movement of 1990 left its legacy for future reconstruction of the state. It empowered citizens to speak out, establishing the possibility that voices might change the destiny of the nation.

7. The Abolition of Monarchy – Birth of a Republic (2008)

In the 21st century, after a decade-long civil war with Maoist guerrillas (1996-2006) that took the lives of over 17,000, came perhaps the most dramatic shift in the context of Nepalese history. The civil war, which had stemmed from inequalities and disenchantment with monarchy, came to an end, with a peace agreement signed in 2006. A nationwide election was held in 2008, and an overwhelmingly Constituent Assembly voted to abolish a 240-year-old monarch. The political architecture of Nepal was forever changed as it was declared a federal democratic republic.

Gyanendra, the last king, was forced out of the royal palace, soon converted to a museum. The key aspect here was the shifting of power into an elected president and prime minister who were tasked with drafting a new constitution. The new constitution eventually came into force in 2015, albeit later than envisaged due to political turmoil and controversies surrounding the process. The abolition of monarchy was not merely the end of royal rule; it was emphatically declaring that Nepal belonged to its people and not to its rulers. While the republic still has its trials facing it, it is now the people who will decide the country’s future.

Final Thoughts

Nepal past is beyond just a number of fight sequences and signing by treaties-it is the saga of aspiration, resilience, and reinvention. Each of those historical moments has been frozen in time by the political institutions and then continues to define the very identity of the nation. The path from the spiritual light of Lumbini to the roar of revolution on the streets of Kathmandu has the proud and poignant history of Nepal.

In the face of modern challenges of economic and social inclusion and political stability, these past experiences illuminate the signs for the nation and mark its remembrance for every Nepali of the strength, unity, and capacity for change. An honor and learning from its past will not serve in building a history for Nepal but a future rooted in wisdom and hope.